For many Austrians the Adriatic Sea is one of the closest and therefore preferred holiday destinations by the sea. For geologists around the world this part of the Mediterranean is a well-studied model system for understanding sequence stratigraphy and how sediments are produced, transported and deposited in an active sedimentary basin. In spring 2017 Rafal Nawrot, who did his PhD at the Department of Palaeontology of the University of Vienna, was hired as a postdoctoral researcher by the Florida Museum of Natural History. He is part of a team that investigates benthic invertebrate communities from the Adriatic Sea back into the last interglacial – some 125.000 years ago – up to today. Their shells are identified and dated to help reveal how geosphere and biosphere interact. In this project specialists in geology, paleoecology, marine ecology and computer modelling join forces for basic research.

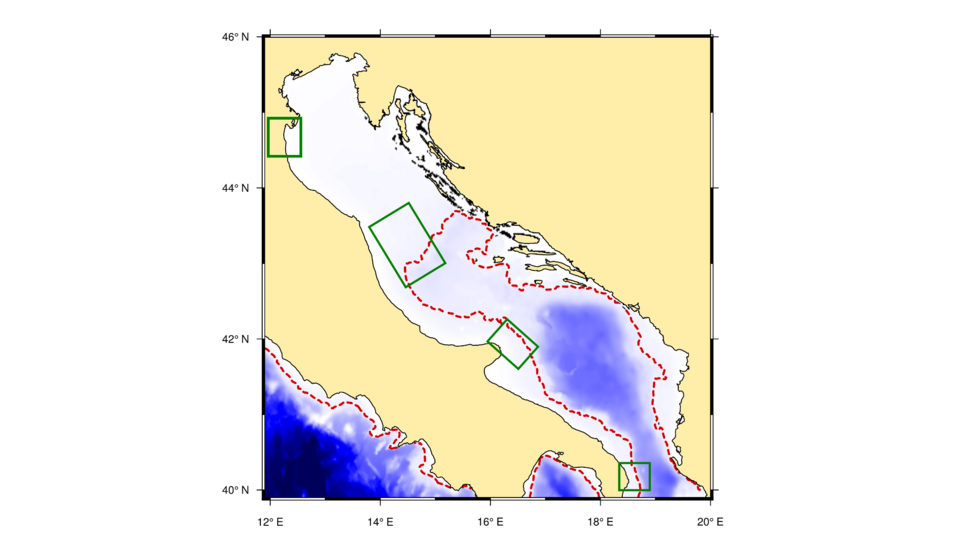

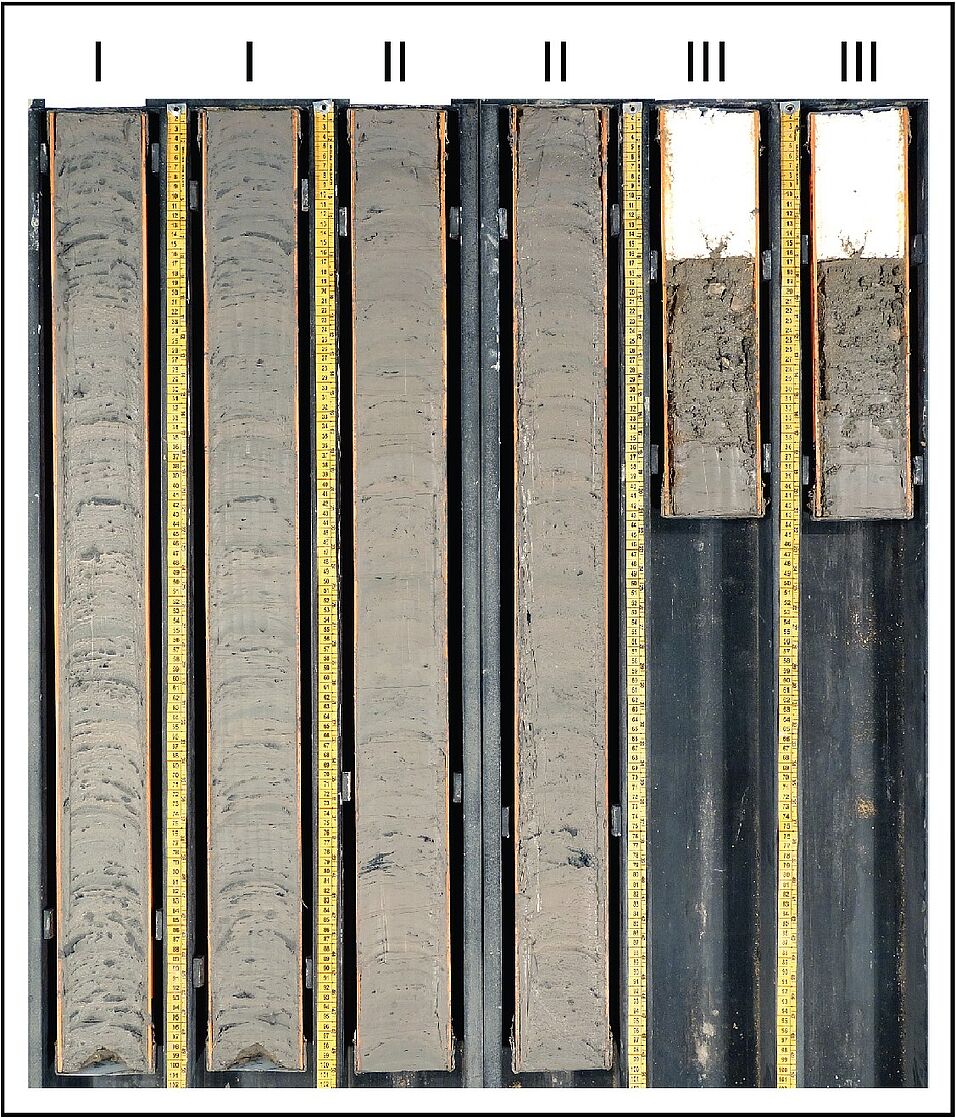

The team in Florida cooperates with the University of Bologna to work on cores from the Po-Plain and Adriatic Sea. The cores stem from different parts of the basin: from the Po river delta of Northern Italy (near Ravenna), down the coast to the southernmost Adriatic Sea (near the Strait of Otranto). They were primarily drilled to explore the geological development of the basin. “Tagged with useful and precise geological and environmental data from previous research, we can now reuse the data and samples to answer our questions”, describes Rafal Nawrot. Sediments and samples from different periods of time are identified and dated with radiocarbon measuring, which is very precise for the past 50.000 years. These are used to reconstruct long-term changes in coastal environments and communities, as well as to detect historical anthropogenic impacts

Learn from the past for the future

The project’s results will be useful for many paleontologists and ecologists around the world as research is geared both towards the near future and the deep past. One goal is to interpret the changes in communities through time, according to changes in climate and sea level in the Adriatic. Fossil assemblages from the last interglacial – the previous time when it was as warm as today – are compared to modern assemblages of species to understand the effects of natural versus man-made impacts for conservation purposes. Rafal Nawrot: “We extract molluscan assemblages from the cores to understand how long-term shifts in marine biota are linked to the evolution of the basin, and the climatic and environmental changes. In this way we can learn for the future”. During the last ice age, when Northern Europe was covered in a giant ice shield, the sea level was much lower and Po river delta was located in the middle Adriatic, almost 300 km to the south from its current position. What is now the Northern Adriatic Sea fell dry during the Last Glacial maximum down to the coastal cities of Ancona (Italy) and Zadar (Croatia). With the onset of the Holocene sea level rise, the shoreline migrated to the current position. „We want to know what happened to the benthic communities and how they coped with the strong changes in sea level and temperature”, the researcher concludes.

Learn from recent past for deep past

The fossils from the Adriatic cores are also used to understand and interpret deep time record correctly. Because fossil record is often patchy and incomplete, shifts in fossil assemblages caused by local environmental changes related to sea level, can be confused with global extinction events. Such artifacts can be weeded out with better understating of factors controlling the quality of paleontological data. Rafal Nawrot: “For our cores we have precise information about sea level, habitat, environment and age. In terms of resolution the data is almost perfect. This means that we can more easily detect biases and identify processes driving them, which will help us to interpret deep time records better”.

Rafal Nawrot met Michal Kowalewski, principal investigator of the research project “Stratigraphic Paleobiology and Historical Ecology of Po Basin”, during his undergraduate studies at the University of Warsaw. “I was lucky to fit the call for an open position right after I finished my work in Vienna. I had practical experience with mollusca taxonomy and had already worked on samples from the Adriatic Sea”. In his dissertation he concentrated on large scale biogeographical patterns involving invasive species in the Mediterranean sea (from the Red Sea via Suez Channel) and geologically recent extinctions (late Pliocene-Pleistocene extinctions starting about 3 Million years ago), in this basin. His doctoral thesis was ranked among the top forty in Austria in 2016 and awarded by the Federal Austrian Ministry of Science. What he works on now is different in methodology and scope, but the main questions are similar. “My main interest is integrating data from the young fossil record and modern biota. We track responses of communities to changes in the climate and how this affects taxonomic and functional diversity. In the most recent parts of the cores we can see the signal of anthropogenic impact”, he emphasizes. Rafal Nawrot hopes that results of the project can also be used to predict stresses on communities related to climate change for conservation purposes in the future.