Students discover Mars mineral in laboratory

Students discover Mars mineral in laboratory

22.10.2025

Earth Sciences students at the University of Vienna have artificially produced an iron sulphate compound in the laboratory and examined its spectral signal. The surprise that followed: this signal matches a spectral signal from Mars that NASA has not yet been able to assign to any known mineral. The Martian mineral 'iron hydroxy sulphate' could now help rewrite the history of the Red Planet. The results have now been published in the journal Nature Communications by an interdisciplinary team with participation of the University of Vienna.

The FeSO4OH compound produced by students in the laboratory turned out to be a Martian mineral. Photo: © Dominik Talla

During laboratory experiments several semesters ago, earth science students at the University of Vienna produced crystals of a new variant of iron hydroxy sulphate, FeSO4OH, which were then analysed in detail: 'The spectral signal of FeSO4OH was particularly striking,' explained Manfred Wildner from the Department of Mineralogy and Crystallography at the University of Vienna.

However, the surprise came later during an exchange with international scientists as part of a research project: 'It turned out that this spectral signal matched exactly with a signal recorded by a Mars satellite that NASA had not yet been able to identify,' said the mineralogist.

Mars satellites examine minerals via light reflection

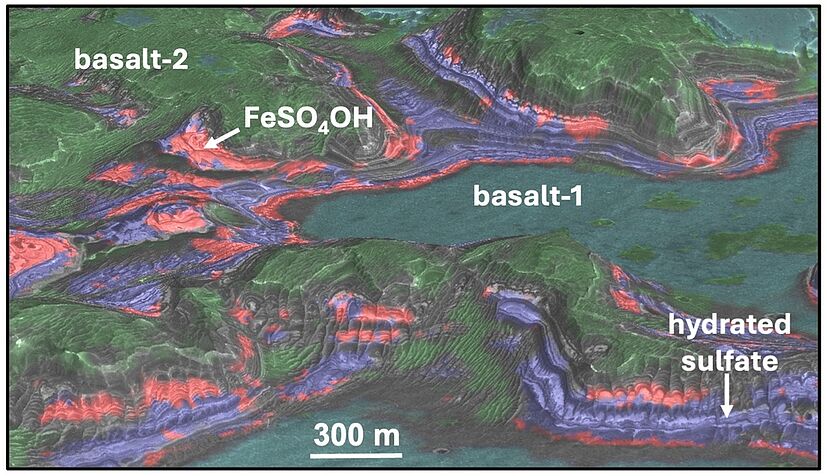

For almost two decades, Mars satellites have been orbiting the red planet and using spectroscopic instruments to analyse the composition of minerals based on their light reflection in the visible and infrared spectral range. At two locations, they found a striking spectral signal that could not be attributed to any previously known substance on Mars. 'We investigated two sulphate-rich locations near the giant Valles Marineris canyon system, which have fascinating geology and whose layered sulphate deposits yielded mysterious spectral bands from orbital data,' said Janice Bishop, senior scientist at the SETI Institute and first author of the paper, which has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

FeSO4OH – the Martian mineral from the laboratory

Mars mineral examined in the laboratory

In a cooperation of mineralogists at the University of Vienna with NASA scientists, this knowledge gap has now been closed. Laboratory experiments showed that at temperatures above 100 °C, a new compound is formed from hydrated iron sulphates such as szomolnokite or rozenite: iron hydroxy sulphate, FeSO4OH. The chemical reaction during its formation changes the structure of the material significantly, and hence also its infrared signal – which explaines the discovery from Mars’ orbit.

Co-author Dominik Talla from the Department of Mineralogy and Crystallography at the University of Vienna. Photo: Dominik Talla

Manfred Wildner from the Department of Mineralogy and Crystallography. Photo: Manfred Wildner

'The experiments have shown that this transformation doesn’t take place without oxygen,' says co-author Dominik Talla from the Department of Mineralogy and Crystallography at the University of Vienna. 'This means that there must have been either local heat sources or geothermal processes on Mars that provided oxygen – volcanic activity, for example.'

Window into Mars' past

Thanks to these chemical peculiarities, researchers can now draw conclusions about the former atmospheric conditions on Mars – and possibly rewrite Mars' history.

Until now, it has been assumed that all geothermal processes on Mars have come to a halt quite early in its history. However, the occurrence of iron hydroxy sulphate in connection with Martian rocks younger than 3 billion years now suggests that heat sources and active chemical environments existed on Mars for a much longer time than previously assumed – and possibly also conditions favourable for microbial life.

Not (yet) a new mineral according to the definition

'In our article, we now postulate that iron hydroxy sulphate exists as a mineral on Mars – but so far there is no physical record of natural origin either from Mars nor from Earth' explains Wildner. Without proven occurrence on Earth, the substance is not (yet) considered a mineral by definition. It is unclear whether the substance can also be found on Earth, as sulphates usually dissolve quickly in rain. 'But on Mars, these compounds can survive for billions of years,' concludes the mineralogist from the University of Vienna.

The researchers now hope that future missions such as “Mars Sample Return” will bring samples from these areas back to Earth. This is the only way to officially confirm FeSO4OH as mineral and determine its role in the history of Mars more precisely.

Publikation:

Bishop, J.L., Meusburger, J.M., Weitz, C.M. et al. Characterization of ferric hydroxysulfate on Mars and implications of the geochemical environment supporting its formation. Nat Commun 16, 7020 (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61801-2